中文摘要

ARDS是重症医学科常见临床综合征,尚无特异性治疗手段,病死率居高不下。根据ARDS病因和严重程度如何进行个体化保护性机械通气和精准治疗是减轻ARDS肺损伤,改善预后的关键。ECMO支持治疗和基于干细胞的生物基因治疗是ARDS治疗的新方向。本文就近年来进展和热点问题进行阐述。

关键词:急性呼吸窘迫综合征;肺保护性通气;驱动压;干细胞;预后;进展

Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a common clinical syndrome in ICU, and the mortality of ARDS remains unacceptably high. ARDS involves a heterogeneous assemblage of pathophysiological processes leading to lung injury. Personalized medicine and precision therapy are the keys to alleviating lung injury, improving the outcome of ARDS patients. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and mesenchymal stem cells have emerged as intervention that may provide more efficacious care to ARDS patients. This review will summarize the current progress on this issue.

Key words: acute respiratory distress syndrome; lung protective ventilation; driving pressure; stem cells; outcomes; progress

急性呼吸窘迫综合征(acute respiratory distress syndrome,ARDS)是常见的临床综合征,近年虽然对ARDS的基础和临床研究不断深入,但其药物治疗等特异性治疗仍未取得突破性进展,治疗主要停留在机械通气等器官支持层面。即使采用肺保护性通气策略等治疗,ARDS病死率仍然高达40%[1]。有效的呼吸功能支持,避免加重肺损伤和促进损伤肺修复是改善ARDS预后的有效措施,也是ARDS治疗重要的研究方向。

一、ARDS仍然是威胁重症患者生命的重要问题

虽然对ARDS病理生理的认识不断加深,采用肺保护性机械通气等支持手段,但ARDS发生率和病死率仍然居高不下。10年来欧洲ARDS的发病率基本维持在5-7.2/10万人之间,低于美国ARDS的发病率(33.8/10万人),尚缺乏近年来中国的流行病学资料。近10年来即使ARDS治疗取得较大进展,病死率仍然维持在40%左右[1]。超过五十个国家459个ICU的流行病学数据显示ARDS患者约占入住ICU患者10.4%,但轻中重度ARDS患者的住院病死率分别为34.9%、40.3%和46.1%[2]。我们进行了各省市20家ICU的流行病学研究调查研究显示入住ICU的重症患者中需要机械通气的约占三分之一;ARDS患者的占入住ICU重症患者约8.2%,住院病死率为34.0%;轻度、中度和重度ARDS患者lCU病死率分别为8.8%、31.1%和56%。ARDS仍然是重症患者的不良预后的严重威胁,需要深入探索预防ARDS发生发展,改善ARDS患者预后的措施和策略。

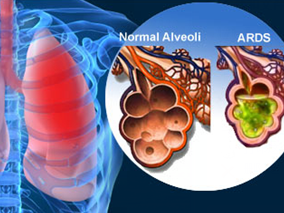

二、ARDS的临床诊断

2012年ARDS新的柏林诊断标准包括急性起病、低氧血症程度、肺水肿来源和影像学表现四个方面。与既往的AECC标准比较,明确了急性起病是指在一周内出现或加重的呼吸系统症状,并将ARDS进行轻、中、重度分层诊断[3],不再保留急性肺损伤的概念,有利于早期发现ARDS,进行早期诊断和治疗干预。

弥漫性肺泡损伤(Diffuse alveolar damage,DAD)是ARDS重要的病理组织学特征,且DAD与ARDS患者预后相关[4]。研究显示跟据柏林诊断标准仅有一半临床诊断ARDS患者经活检证实存在DAD,存在DAD的ARDS患者氧合更差,顺应性更低,对治疗反应不佳[5],患者预后更差[6]。存在DAD的患者有可能是ARDS的一个特殊亚型,采用针对性的治疗有望改善这部分患者预后。

ARDS柏林标准分层诊断可反映ARDS患者疾病严重程度,并可预测患者预后。与AECC标准相比,柏林标准能有效细化ARDS的严重程度,有利于分层诊断和早期治疗;分层诊断也为临床分层治疗提供了依据[7]。ARS严重程度越高,死亡率越高,机械通气时间明显延长。根据柏林诊断标准,患者轻度ARDS患者病死率为10%,中度为32%,重度ARDS病死率高达62%,接受机械通气的中位时间随着病情严重程度而逐渐延长(分别为5天、7天和9天)。采用诊断ARDS 24小时后的FiO2和氧合指数进行再次评估有利于预后的判断。ARDS患者存在明显的肺损伤不均一性,不同ARDS患者对治疗的反应不同,ARDS治疗24h后氧合情况对患者的预后具有良好的预测价值[8]。

三、强调ARDS患者病因治疗和个体化精准治疗

ARDS是各种致病因素导致的临床综合征,病因和发病机制多种多样,对治疗的反应和预后也不尽相同,不可能用一种治疗来解决所有问题。肺内和肺外原因导致的ARDS患者呼吸力学和对肺复张等治疗的反应均不相同[9, 10],应采用不同的治疗策略。根据患者病因和病理生理机制采用个体化的治疗是改善患者预后的重要因素。ARDS患者婴儿肺概念提示大量肺泡塌陷,可通气肺容积明显减少是ARDS重要的病理生理特征[11]。随后多中心临床证实发现小潮气量保护性通气改善ARDS预后[12]。根据ARDS患者理想体重采用保护性机械通气已经成为临床共识,但机械通气第一天小潮气量通气比例仅54.4%,保护性通气依从性仍需要进一步提高[13]。对于部分重度ARDS患者,即使采用小潮气量通气仍存在肺泡过度膨胀,导致肺损伤[14]。重度ARDS患者可能需要采用超保护性机械通气,以减轻通气相关肺损伤[15],以期改善ARDS患者预后。因此,首先需要对ARDS患者进行评估,肺内还是肺外原因导致的ARDS,患者炎症反应的强弱,是否存在DAD,是否存在基因异质性,并评估肺可复张性,根据患者个体差异选择合适的治疗方法[16],进行个体化精准治疗。

四、应力导向的ARDS肺保护通气策略

肺应力也就是跨肺压是真正扩张肺组织的力量,引起VILI的始动因素是过大的肺应力,因此应力导向的保护性通气策略才有可能从根本上减轻肺损伤[17],改善患者预后[18]。对9个随机临床研究(3562例ARDS患者通气策略相关研究)数据进行再分析,采用多变量调整的标准风险分析和多层中介效应分析评估机械通气参数与ARDS患者预后的关系,研究发现在机械通气相关变量中,驱动压(ΔP)与患者的预后密切相关[19]。增加ΔP与患者死亡率恶化显著相关,其相对死亡风险达1.41,降低潮气量可避免ΔP过高,数据模型显示ΔP在15 cmH2O以下可降低死亡风险,但需要进一步随机对照临床研究证实。

五、优化ARDS肺复张策略

肺复张是ARDS患者改善氧合,维持肺容积,减轻肺损伤的重要手段。可复张性(recruitability)是指ARDS肺组织具有的可被复张并且保持开放的能力[20],肺可复张性评估是ARDS患者是肺复张及PEEP设置的前提[21]。ARDS患者之间肺组织的可复张性差异很大,可复张的肺组织从几乎可以忽略到超过50%不等,均值约为13±11%[22]。可复张性低的ARDS患者即使采用肺复张手法也很难实现塌陷肺组织的开放,肺复张还可能导致过度膨胀,也无需设置高PEEP。反之,对于可复张性高的患者,肺复张及高PEEP可能有益[23]。对有肺可复张性的重度ARDS患者,应采用肺复张和较高水平的PEEP,并关注患者氧合等对治疗的反应。

俯卧位通气也是一种广义的肺复张,重度ARDS早期俯卧位通气可改善患者预后。其机制与体位改变塌陷肺泡由背侧转向腹侧,改善肺组织压力梯度,明显减少背侧肺泡的过度膨胀和肺泡反复塌陷-复张、改善局部肺顺应性和肺均一性[24]、改善氧合,改善通气血流比值,减轻心脏的压迫等有关[25]。研究显示对于严重低氧血症(PaO2/FiO2<50 mmHg,FiO2≥0.6,PEEP≥5 cmH2O)的ARDS患者,早期长时间俯卧位治疗显著降低病死率[26]。俯卧位通气需要有经验的团队实施,以期减少并发症,改善预后。

采用缓慢的肺复张方法如PEEP递增法,俯卧位或APRV[27]等模式进行肺复张可能改善肺复张的均一性,可能达到肺复张目标,减轻肺损伤;并避免持续性肺膨胀(SI)等快速肺复张方法的不良反应[28],如循环干扰、人机不同步、气胸和肺内气体分布不均一导致的肺泡过度膨胀。

六、轻度ARDS可尝试高流量氧疗和无创通气

轻度ARDS患者可尝试采用高流量氧疗和无创通气。预计病情能够短期缓解的早期ARDS的患者和合并有免疫功能低下的ARDS患者早期可尝试NPPV治疗。对于轻度ARDS患者,无创通气成功率可达70%,NPPV明显改善轻度ARDS病人的氧合,有可能降低气管插管率,有改善患者预后趋势[29]。当ARDS患者存在休克、严重低氧血症和代谢性酸中毒,常常预示NPPV治疗失败。NPPV期间需要严密监测,观察1~2 h后病情不能缓解迅速转为有创通气。

高流量氧疗在轻度ARDS患者的应用逐渐引起重视。随机对照临床研究显示与无创通气和常规氧疗比较,高流量氧疗降低无创通气相关并发症,改善低氧血症,改善高碳酸血症,降低气管插管率,甚至降低90天病死率[30],降低拔管后再插管率[31],需要注意的是延迟插管明显增加患者的病死率[32]。高流量氧疗对ARDS患者预后的影响需要进一步临床研究证实。

七、ECMO成为ARDS的一线治疗

ECMO已经成为ARDS规范化治疗中重要的治疗手段。在保护性通气基础上,充分肺复张等措施仍无效的重症ARDS患者,若病因可逆、应尽早考虑ECMO,病因可逆的早期重症ARDS患者通过ECMO治疗可改善预后[33, 34]。但总体来说ECMO治疗重度ARDS患者病死率仍较高[35],ECMO最佳适应人群,合理的干预时机和管理策略,撤离方式和时机等仍需要进一步探讨。仍需要规范ECMO临床应用并在经验的中心进行EMCO治疗以期改善患者预后[36]。随着体外膜肺氧合材料技术的进步,ECMO和体外清除技术已成为ARDS的一线治疗手段。

八、基因治疗走向临床

间充质干细胞移植治疗和基因治疗仍是ARDS极具潜力的治疗方法。给肺损伤的动物或患者移植MSC后,MSC可在肺内分化为Ⅱ型肺泡上皮细胞,后者可进一步分化为Ⅰ型肺泡上皮细胞,另外归巢到肺内的间充质干细胞可通过旁分泌途径作用于损伤肺,减轻肺组织损伤、减轻肺纤维化,尽早恢复肺泡上皮细胞或内皮细胞功能,目前仍处于实验研究阶段[37]。携带不同基因的间充质干细胞能促进干细胞在肺内的归巢和分化[38],减轻炎症反应,改善ARDS动物模型的肺损伤[39]。间充质干细胞治疗中重度ARDS的一期临床试验显示中重度ARDS患者对间充质干细胞耐受性好,未见明显不良反应[40]。干细胞移植和基因治疗携带何种关键基因、自身免疫反应、远期效果和不良反应均需要进一步探索。

与其他器官相比,干细胞移植治疗肺部疾病起步较晚,应用于临床尚有许多问题亟待解决,如间充质干细胞进入肺脏后如何增加在肺内的归巢?局部微环境(Niche)对间充质干细胞的分化的影响如何?如何对移入的干细胞生存和分化进行控制?相信在不久的将来干细胞移植和基因治疗一定会为ARDS的预防和治疗开辟新篇章。

九、ARDS的远期预后

ARDS患者的远期预后包括患者躯体和精神状况,如远期的肺功能、神经功能运动功能和等。ARDS患者早期患者即可存在ICU获得性肌肉无力,机械通气相关膈肌功能障碍,重症神经肌肉病变和认知功能障碍等问题影响患者远期预后,需要患者逐步进行康复[41]。ARDS患者在疾病好转后较长时间内都存在心理和精神健康问题,随访发现ARDS患者5年后肺功能可大致恢复,部分弥散功能障碍,运动受限[42]。关注ARDS患者出院后躯体精神状态、工作能力、生活质量及对经济家庭等等带来的影响,改善ARDS患者远期预后。

总之,在ARDS分层诊断和评估的基础上进行个体化的保护性通气和个体化精准治疗,以期减轻肺损伤,改善ARDS患者预后;采用ECMO进行支持治疗和基于干细胞的基因治疗是ARDS新的治疗方向,仍需临床进一步优化和探索。

References

[1] Villar J, Sulemanji D, Kacmarek RM. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: incidence and mortality, has it changed. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014. 20(1): 3-9.

[2] Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016. 315(8): 788-800.

[3] Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012. 307(23): 2526-33.

[4] Cardinal-Fernández P, Bajwa EK, Dominguez-Calvo A, Menéndez JM, Papazian L, Thompson BT. The presence of diffuse alveolar damage on open lung biopsy is associated with mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016 .

[5] Guerin C, Bayle F, Leray V, et al. Open lung biopsy in nonresolving ARDS frequently identifies diffuse alveolar damage regardless of the severity stage and may have implications for patient management. Intensive Care Med. 2015. 41(2): 222-30.

[6] Lorente JA, Cardinal-Fernández P, Muñoz D, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with and without diffuse alveolar damage: an autopsy study. Intensive Care Med. 2015. 41(11): 1921-30.

[7] Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012. 38(10): 1573-82.

[8] Villar J, Fernandez RL, Ambros A, et al. A clinical classification of the acute respiratory distress syndrome for predicting outcome and guiding medical therapy*. Crit Care Med. 2015. 43(2): 346-53.

[9] Rocco PR, Pelosi P. Pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome: myth or reality. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008. 14(1): 50-5.

[10] Thille AW, Richard JC, Maggiore SM, Ranieri VM, Brochard L. Alveolar recruitment in pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome: comparison using pressure-volume curve or static compliance. Anesthesiology. 2007. 106(2): 212-7.

[11] Gattinoni L, Pesenti A. The concept of "baby lung". Intensive Care Med. 2005. 31(6): 776-84.

[12] Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342(18): 1301-8.

[13] Weiss CH, Baker DW, Weiner S, et al. Low Tidal Volume Ventilation Use in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016. Mar 31. [Epub ahead of print].

[14] Terragni PP, Rosboch G, Tealdi A, et al. Tidal hyperinflation during low tidal volume ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007. 175(2): 160-6.

[15] Terragni PP, Del SL, Mascia L, et al. Tidal volume lower than 6 ml/kg enhances lung protection: role of extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal. Anesthesiology. 2009. 111(4): 826-35.

[16] Goligher EC, Kavanagh BP, Rubenfeld GD, Ferguson ND. Physiologic Responsiveness Should Guide Entry into Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015. 192(12): 1416-9.

[17] Chiumello D, Carlesso E, Cadringher P, et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. 178(4): 346-55.

[18] Talmor D, Sarge T, Malhotra A, et al. Mechanical ventilation guided by esophageal pressure in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2008. 359(20): 2095-104.

[19] Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372(8): 747-55.

[20] Caironi P, Carlesso E, Cressoni M, et al. Lung recruitability is better estimated according to the Berlin definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome at standard 5 cm H2O rather than higher positive end-expiratory pressure: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2015. 43(4): 781-90.

[21] de Matos GF, Stanzani F, Passos RH, et al. How large is the lung recruitability in early acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective case series of patients monitored by computed tomography. Crit Care. 2012. 16(1): R4.

[22] Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006. 354(17): 1775-86.

[23] Goligher EC, Kavanagh BP, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Oxygenation response to positive end-expiratory pressure predicts mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome. A secondary analysis of the LOVS and ExPress trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014. 190(1): 70-6.

[24] Cornejo RA, Díaz JC, Tobar EA, et al. Effects of prone positioning on lung protection in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013. 188(4): 440-8.

[25] Gattinoni L, Taccone P, Carlesso E, Marini JJ. Prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Rationale, indications, and limits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013. 188(11): 1286-93.

[26] Guerin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013. 368(23): 2159-68.

[27] Roy S, Habashi N, Sadowitz B, et al. Early airway pressure release ventilation prevents ARDS-a novel preventive approach to lung injury. Shock. 2013. 39(1): 28-38.

[28] Chiumello D, Algieri I, Grasso S, Terragni P, Pelosi P. Recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome and during general anesthesia. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016. 82(2): 210-20.

[29] Zhan Q, Sun B, Liang L, et al. Early use of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute lung injury: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2012. 40(2): 455-60.

[30] Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372(23): 2185-96.

[31] Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of Postextubation High-Flow Nasal Cannula vs Conventional Oxygen Therapy on Reintubation in Low-Risk Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016. 315(13): 1354-61.

[32] Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim CM, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015. 41(4): 623-32.

[33] Zangrillo A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Landoni G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with H1N1 influenza infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis including 8 studies and 266 patients receiving ECMO. Crit Care. 2013. 17(1): R30.

[34] Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009. 374(9698): 1351-63.

[35] Karagiannidis C, Brodie D, Strassmann S, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: evolving epidemiology and mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2016. 42(5): 889-96.

[36] Combes A, Brodie D, Bartlett R, et al. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014. 190(5): 488-96.

[37] Devaney J, Contreras M, Laffey JG. Clinical review: gene-based therapies for ALI/ARDS: where are we now. Crit Care. 2011. 15(3): 224.

[38] Cai SX, Liu AR, Chen S, et al. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling promotes mesenchymal stem cells to repair injured alveolar epithelium induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015. 6: 65.

[39] Hu S, Li J, Xu X, et al. The hepatocyte growth factor-expressing character is required for mesenchymal stem cells to protect the lung injured by lipopolysaccharide in vivo. Stem Cell Res Ther. 7(1): 66.

[40] Wilson JG, Liu KD, Zhuo H, et al. Mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells for treatment of ARDS: a phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015. 3(1): 24-32.

[41] Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016. 42(5): 725-38.

[42] Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011. 364(14): 1293-304.

相关链接:

东南大学附属中大医院副院长,重症医学科主任,博导,中华医学会重症医学分会主委、江苏省重症医学会主任委员、中国病理生理学会危重病医学专业委员会全国常委、江苏省中西医结合学会急诊专业委员会主任委员。《中华急诊医学杂志》副总编、《中华创伤杂志英文版》、《中华内科学杂志》等6个杂志的编委。

免责声明

版权所有©人民卫生出版社有限公司。 本内容由人民卫生出版社审定并提供,其观点并不反映优医迈或默沙东观点,此服务由优医迈与环球医学资讯授权共同提供。

如需转载,请前往用户反馈页面提交说明:https://www.uemeds.cn/personal/feedback

作者:邱海波主委 东南大学附属中大医院副院长

编辑:环球医学资讯 贾朝娟

Copyright © 2025 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2025 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.